The judges for the 2023 Telstra NATSIA Awards have maintained what seems to be becoming something of a tradition in their selection of the ‘Big Telstra’ winner. It literally has to be big, innovative, rooted in tradition, but not necessarily brilliantly aesthetic. Think the collaborative Tjanpi Toyota from the Deserts, Dennis Nona’s mighty Torresian bronze crocodile and last year’s life-size woven Makassan sail from Milingimbi.

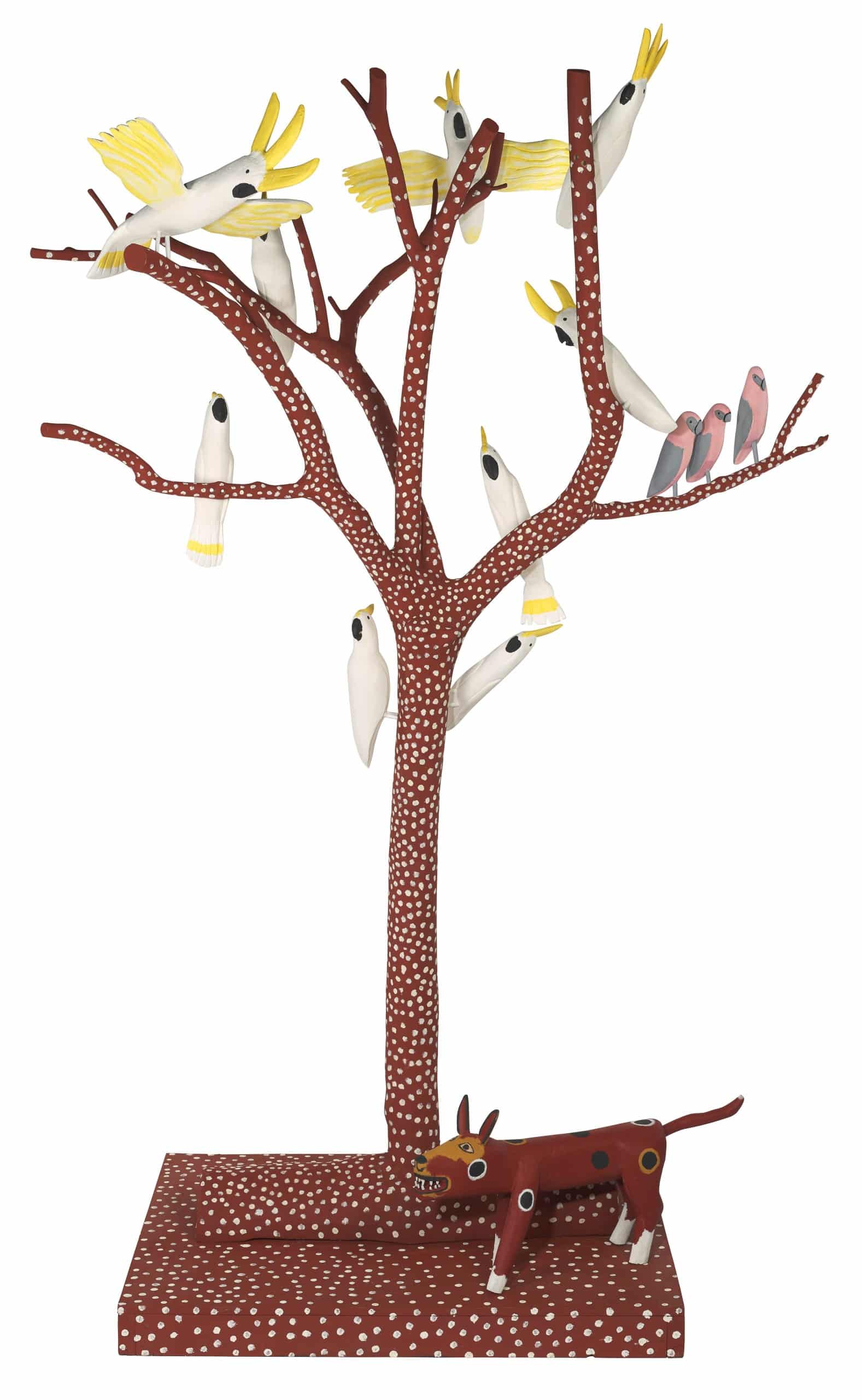

This year it’s a Wik-Munkan tree by Keith Wikmunea, a Thu’ Apalech man and artist from Aurukun on Cape York for an almost 3 metre tall sculptural piece, Ku’, Theewith & Kalampang: The White Cockatoo, Galah and the Wandering Dog. His tree is the winner of the top Telstra Art Award valued at $100,000.

Wkimunea’s explanation: “It is a sculpture that represents who I am as a Thu’ Apalech man from the Cape York Peninsula. The colours on this tree are specific to my clan. In Wik-Mungkan, my first spoken language, we call this tree yuk thanchal. This tree is also known as milkywood [sic] in English and is the same tree that my ancestors have been using since the beginning of time to create their artefacts. My Puulwuy [father’s totem] and my Kathwuy [mother’s totem] are represented here too”.

And the milkwood auwa (totem centre) lies in the heart of Wik Mungkan Country, between the Archer and Kendall Rivers.

Judging the NATSIAAs this year were Larper man, Dr Peter Yanada McKenzie, a practising photographer, curator, musician, project manager and university lecturer; Kelli Cole, a Warumunga and Luritja woman from central Australia who is Curator of Special Projects at the National Gallery of Australia; and Torresian/Naarm woman Janina Harding – former Artistic Director of CIAF who continues as Indigenous programs manager for the City of Melbourne.

Their comments on the winner: “The extraordinary scale and presence of Ku’, Theewith & Kalampang reveals the master carver at work. The remarkable execution of the work captures the strong sense of community life that invites the viewer to enjoy”.

The most prominent name in the list of the other winners is Owen Yalandja – Maningrida’s master of the carved Yawk Yawk. Otherwise, the judges seem to have searched far and wide to discover newish names. Potter Anne Nginyangka Thompson, for instance, winning the 3D award; painter Julie Nangala Robertson may have had a famous mother in Dorothy Napangardi, but she’s really emerged here to take the General Painting award; Jimmy John Thaiday may have won last year’s multi-media award, as he has again – but he’s better known on Erub Island than in Darwin; Brenda L Croft has renown as a curator and academic, but it’s her photographic self-portrait that has won her the Works-on-Paper award; and one wouldn’t expect to know the Emerging Artist, but predictably Dhalmula Burarrwaŋa comes from the Buku-Larrnggay art centre in Yirrkala.

“When I am painting, my mind doesn’t go this way or that way. It stays in one place and it’s quiet”, a wonderful quote from Owen Yalandja, who’s quiet mind has broken free from carving to win the Best Bark award, stunning the judges: “We felt that the overall execution and intricacy of Ngalkodjek Yawkyawk was breathtaking. The depth and detail of this work gives the illusion of the shimmering of mermaid scales on the undulation of the bark”.

Julie Nangala Robertson must have Mina Mina in her blood, but she paints it with a fascinating filmy blend of stylised experimentation and ancient narrative. The judges noted: “She paints her mother’s Jukurrpa stories, stories that have been passed down to her by her mother and all the mothers before her for millennia. We feel this painting captures the essence of water, ceremony and a Dreaming story that has existed for millennia”.

Coming from the eastern edge of the Torres Strait, Jimmy John Thaiday knows his sea: “The ocean is always changing, shifting, and moving. The tides, waves, wind, and currents of the ocean bring us food and shape our culture. The ocean is mysterious – many secrets lie just beneath the surface. We must respect the ocean’s power; it can provide for us, but also take life away. I am exploring the way the ocean creates cycles of life, death, and rebirth. If we resist these forces, we can suffer. When we let go, then we can let nature take its course, and things will be in balance”.

And the judges’ reason for returning to the well two years running: “Ethereal and emotive, the imagery of Jimmy John Thaiday being caught and strangled by the ghost nets is haunting”.

Ernabella’s Anne Nginyangka Thompson continues that art centre’s expertise with ceramics, but the artist adds a critical slice of Anangu History: “Before, it was a beautiful landscape without problems like we have today. People were connected as families. Everything was silent. Everyone looked after the animals and the environment. People don’t have that life anymore.We’ve got houses now, a clinic, bitumen roads and everyone is driving cars. We were given flour, sugar and tea and now everyone is getting diabetes. In our life in the old days the food was healthy, it was natural. Now people are passing away from diabetes and sugar and smoking”.

The judges added: “We were informed by the impact of change through the bright orange glaze and reminded how it’s hard to come back to the old ways of living on Country because of what is deemed ‘progress’”.

Brenda L Croft’s photographic portraits of Aboriginal women have already been admired in the Sydney Festival and The National exhibition; here she’s added a family dimension: “Matrilineal/patrilineal blood/memories connect my son/nephew and I (sic), through his mother and my father. Our First Nations heritage grounds us in continuous, ever-shifting colonised landscapes; literal, metaphorical and metaphysical. Ironically, it is our non-Indigenous ancestor who inextricably binds us to each other, my grandfather and his great-great-grandfather”.

Emerging artist Dhalmula Burarrwaŋa explains: “There is a Yolŋu slang saying ‘wanha, dhika, nhawi?’ (which is the title of her work on barks). Or it could be ‘dhika, wanha, nhawi?’or even ‘nhawi, dhika, wanha?’ This is the Yolŋu idiomatic slang you can mutter (or shout) when you have lost your key, lighter, toothpaste, calculator, smokes, spear, water bottle, woomera, knife, oysterpick, torch, trowel, anchor, bag, cat, spoon, dog, cup, pen, toothbrush, axe, clapstick, scissors, car, pot, wallet, keycard, phone, etc”.

The judges obviously laughed: “We were heartened by the fun and playfulness the images capture in everyday life”.

And the judges were clearly moved to add a Highly Commended award for Balwaldja Wanapa Munuŋgurr’s work on paper, Exile (2023). For the artist has been exiled to Darwin following one of those family disputes in his Yolŋu family. His work maps beloved homelands that he may never see again.

I should explain that following recent hospitalisation, I have not been able to be in Darwin for the great event this year. So I’m reliant on electronic images to appreciate the NATSIAA results. But it’s worth noting that the winners overcame finalist entries from previous award winners such as Frank Young, Guynbi Ganambarr, Alick Tipoti and Iluwanti Ken.

It’s also worth noting my impressions of works amongst the 63 finalists that might have deserved an Award had I been judging! Betty Campbell’s danced and sung Women’s Story from Mimili is a stunner. Dhopiya Yunupingu has somehow managed to recreate traditional Yolŋu dance materials representing Makassan flags and sails as a painting on bark. Jahkarli Felicitas Romanis has decolonised a Norman Tindale photo of her great-grandmother to allow herself Pita Pita identity in her multi-media entry. And Eileen Bray has brought delightful clarity and simplicity to her painting of a Gija boab birthing tree.

Another amazingly textured bark from Yolŋu Country turned up in the Salon des Refuses according to my spies. Milminyina Dhamarrandji has totally created the feel of a ceremonial sand sculpture dedicated to the Songline of the Death Adder.

How did it escape the Telstra pre-selectors’ attention?