“Myth – Traditional story, usually concerning some superhuman being or alleged event which attempts to explain natural phenomena; especially a traditional story about deities and the creation of the world and its inhabitants. Hence, any invented story”.

So says the Macquarie Dictionary. Though I wonder whether the headline writers of two recent online stories about myth in Indigenous art checked out that definitive source. ‘Aboriginal Art Explained, Myths Busted’ asserts the ABC; while the American Cultured Magazine declares that a show called ‘Iwantja Rock’nRoll’ ‘Eschews The Modernist Myth of Aboriginal Art’.

At the ABC, the excellent Rudi Bremer, presenter of the Radio National ‘Awaye’ program, begins by mythmaking herself. “Prior to colonisation, the entire world was a canvas for creating Indigenous art”. Surely that word ‘art’ simply didn’t enter the many Aboriginal lexicons until c1971, when it was found that traditional symbols and motifs, timeless in their usage to teach the foundation myths and rules of fiercely disciplined societies, could also be reproduced for a white marketplace, where they could earn money.

Indeed, Bremer acknowledges just such a distinction when she continues, “Through song and dance, through the production of objects like shields and coolamons, and on bodies and surfaces, Indigenous communities recorded and communicated histories, traditions, beliefs, concerns and celebrations”. Some might call them myths. But few, pre-1971 would diminish those efforts as mere ‘art’.

This is all part of Myth 1 – The Myth of Aboriginal Art History. Which then attempts to pre-date the emergence of Papunya Tula in 1972 by citing William Barak, Tommy McRae and Micky of Ulladulla in the 19th Century as examples of the quick adoption of ‘art’. Then, or course, there was Albert Namatjira. But all four adopted the techniques of Western art, none employing traditional or ceremonial designs. And the traditional barks were also collected from the 19th Century on – but rarely as art, rather as ethnography, to understand a culture that was expected to disappear.

So I’d argue that it’s not really a myth that ‘art’ began in 1971 at Papunya, it’s a fact.

Myth 2 – “Indigenous art is solely ‘traditional’. For example, an artist from the Central Western Desert might use the ‘u’ shape to symbolise ‘man’, but if they’re painting with acrylic paint rather than ochres, they may not consider their work to be an example of traditional Indigenous art”.

Oh dear! If only Mick Namarari, Long Jack Phillipus or Emily Kngwarrey were still around to refute this rejection of tradition. For even when painting in acrylics, weaving in Tjanpi grasses, painting on the backs of road signs or making moulded metal sculptures, an artist may still be telling a traditional story with due reverence. Indeed, the example cited by Rudi Bremer – Mrs D Yunupingu’s mermaids, which just won the Best Bark at the Telstra NATSIAAs – may appear to challenge Yolngu tradition, but is in fact backgrounded by a complex story of how Mrs Yunupingu’s future identity was communicated to her father as he killed a fish!

And of course Yolngu rules about ochres don’t apply across the Deserts, Kimberley, etc

More upsetting still is the contribution of Bruce McLean, Assistant Director for Indigenous Engagement at the National Gallery. “When tourists started showing an interest in Aboriginal art, people from those areas were given books of paintings from the Central Desert, or books of bark paintings from Arnhem Land. They were basically forced to copy them,” he asserts.

Who were these tourists??? And, while not denying that some art advisers saw it as their job to share the wider world of art with their community artists (remember Rover Thomas’s thoughts on Mark Rothko – ‘Who’s this bloke who paints like me”!), this is Ooga Booga stuff! McLean goes on to tout (Richard) ‘Bell’s Theorem’ which first put into print that outrageous idea that remote/classical artists were just knocking out tourist tat and that he was the real Aboriginal artist of today as he appropriated other Western artists’ styles.

Which brings me to the distinction that the great English art critic Herbert Reade made in the 1930s. In his book, Art Now, he posited the value of the ‘Innocent Eye’ over the ‘Instructed Eye’, allowing the object to become a “point of departure for the production of lines and colours that are entirely subjective in origin”. He was admiring the new world of abstract art. But he might just as well have been referring to the genius of Emily Kngwarreye, whose untrained ‘Innocent Eye’ produced work that we can read as abstract, though for her was loaded with specific meaning.

Richard Bell’s ‘Instructed Eye’ from his art college background is a totally different, equally Indigenous thing. But I do wonder whether he and ‘Oooga Booga’ Emily should be hung on the same wall?

For he has surely not had the benefits adduced by Indigenous artist and curator Tess Allas, who is quoted in the ABC article as discerning, “I firmly believe that there is an undocumented greater influence (than those tourist art books), and that is of traditional family and community artists who transfer their knowledge to the generations under them”. How very percipient

Myth 3 – “It’s always readable”, ie it has a story any viewer could discover? “This means a casual viewer might only have a basic understanding of a work, while somebody who is initiated into the artist’s community holds a deep understanding of it”. Is this a myth or a fact???

It’s not only an anthropological interest that creates the desire to understand a painting – surely, behind the aesthetic appreciation for any collector comes a desire to go deeper, whether it’s Turner, Rothko or Xiao Lu? Prof Ian McLean is quoted as noting that “the Papunya Tula artists particularly in more recent decades, who’ve taken to titling their work ‘untitled‘, to make the point that people should be considering these paintings as works of art first and foremost.” But Emily never titled her works – merely waving her hands and declaring “Whole thing” when anyone dared to ask the meaning of her paintings. Yet every auction house invents its own title today, which suggests that they think meaning matters!

Myth 4 – “It’s overpriced” – which is only a myth if you don’t bother to compare with the investment grade prices attached to Western and Chinese art these days. Arguably First Nations art is just beginning to establish value, encouraged by overseas exposure (see below) which is much more appreciative than Australia. Here people are still battling to come to a real understanding of cultures that they spent so long dismissing out of hand.

Myth 5 “Ethical buying is hard work”. Certainly, it should not be difficult. But some complexity lies in an increasing pressure today to buy directly from art centres. They’re essential organisations, but they also sell to dealers who have galleries in places where you can actually go and build up an appreciation of the art. Not all of us can either choose to fly to the remote sources or choose to buy online without seeing a work physically. And of course, both art centres and galleries charge a premium for their efforts.

The secret is to be unafraid to ask questions, and I note that the Indigenous Art Code has developed seven questions they recommend buyers ask when purchasing Indigenous art. And the Code encourages, “Most dealers in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art have high ethical standards and a genuine sense of responsibility to Indigenous artists and their communities”.

A much more confident, less nervous approach to contemporary Indigenous art seems to pertain in the US and Europe. Fired by shows such as the start in New Hampshire of a national American tour of ‘Madayin‘, historic and contemporary barks from the Yolngu in Yirrkala, commentary is equally bold. While in Munich, a sensational collection of 170 barks from right across the north that were put together by a German dermatologist between 1969 and 2015, has a catalogue to match. In Vienna, the Weltmuseum Wien has just been gifted 58 Aboriginal artworks, with works by 40 artists including (their spelling) John Maurendjoel, Melba Gungarwanga, Charlie Genmalala Priyanswe, Lena Yarinkura, and Marie Borontatamiri. And at the Lyman Allyn Museum in Connecticut, Gloria Petyarre and Emily Kngwarreye are on show as influiences on the man who invented conceptual art, Sol LeWitt. And the Kluge/Ruhe Musuem in Virginia has mounted not one but two exhibitions – as no public institution has managed in Australia – to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Papunya Tula Artists.

But it’s the New York show of art from the Iwantja Art Centre in Indulkana that takes the cake in terms of inspiring amazing – and amazed – commentary. The author is Henry Dexter from Cultured Magazine, and it’s clear that the art – he wisely prefers the term ‘mark-making’ – of Vincent Namatjira, Kaylene Whiskey, and Tiger Yaltangki at the Meatpacking District’s Fort Gansevoort Gallery has excited his phagocytes:

“In recent years, the massive critical reappraisal of Australian Aboriginal art, a rich and radically singular tradition of mark making that’s history spans thousands of years into the pre-colonial past, has returned the vigorous spontaneity of a gestural language composed of swirling dashes and dots to the collective mind of the contemporary art world. Undeniably, this outburst of renewed interest and attention owes something to our persistent fascination in the West with the aesthetic achievements of 20th-century modernism, perhaps chief among them Abstract Expressionism and process art. The immediate visual similarity between the works of now thoroughly canonized legends of the last century’s aesthetic avant-gardes like Jackson Pollock or Yayoi Kusama on the one hand, and the pulsating cosmic spirals that blossom on cave walls, tree bark, clothing, and musical instruments throughout the Australian continent on the other, threatens to contaminate our understanding of the unique artistic propositions made by Aboriginal painting.

“A new generation of Indigenous artists whose exuberantly political work, saturated with personality and wit, befuddles the modernist mythos of purity and isolation that dominates so many conversations about Aboriginal abstraction.

“Paintings by Vincent Namatjira, Kaylene Whiskey, and Tiger Yaltangki, (are) the multi-generational trio of Aboriginal image makers’ take on the symbolic authority of empire, metabolizing cultural icons as thoroughly and synonymously American as the Statue of Liberty, Wonder Woman, the Route 66 highway marker, as well as authority’s ultimate figurehead herself: Queen Elizabeth, in expressive flurries of brightly hued acrylic. Namatjira’s playful flirtation with the cultural products of their colonizers enlivens our understanding of their political conditions. It speaks truth to the utter absurdity of their history, which were it not devastatingly horrific might just be hilarious.

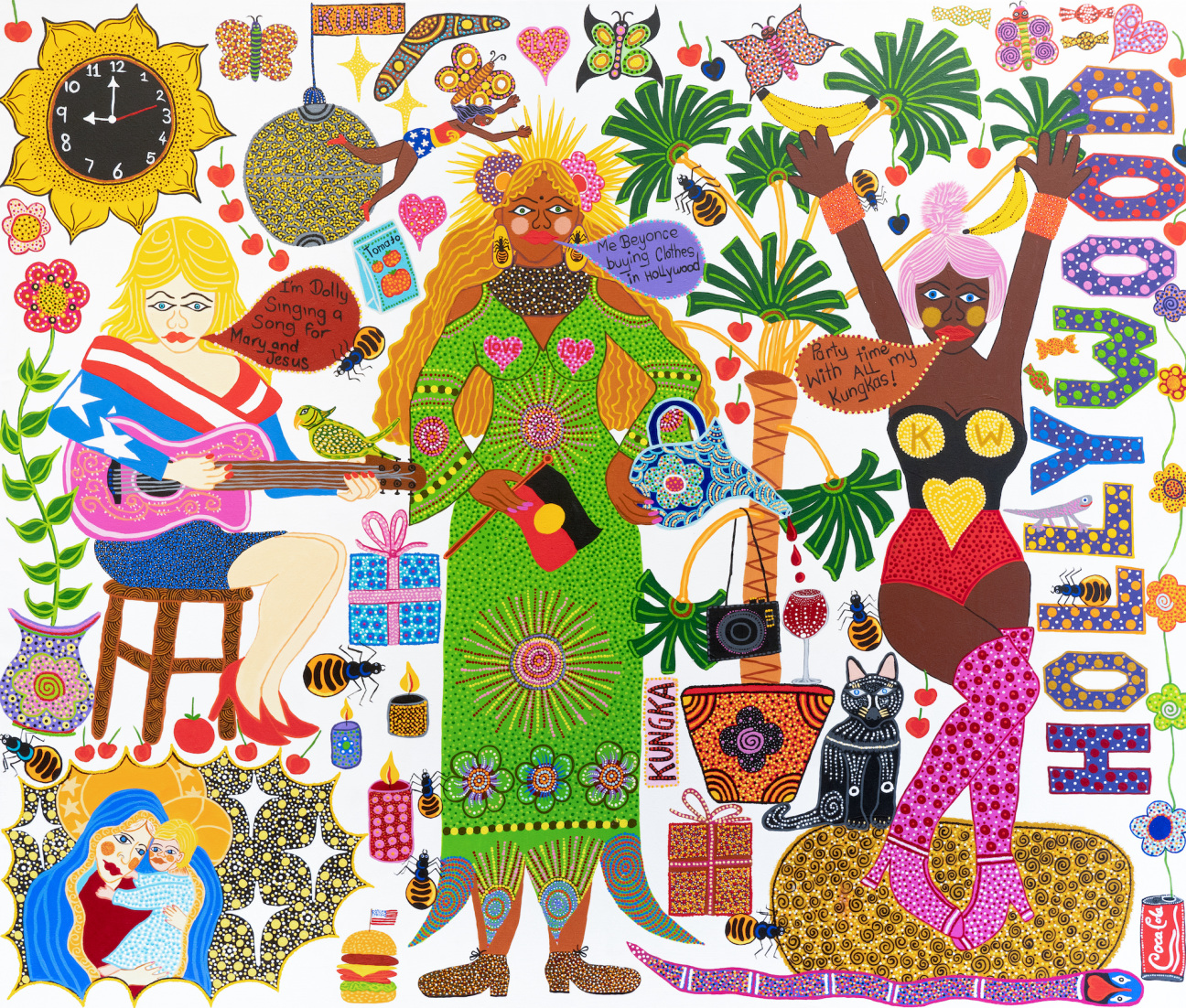

“In Whiskey’s highly stylized psychedelic compositions that she describes as bringing “the comic to the canvas” for example, female popstars are adorned with the region’s traditional dot-paintings, a technique Whiskey learned too from her “grandfather, mother, and aunties.”

“Yaltangki’s paintings too combine mythological characters from the spiritual world of the Anangu with our own contemporary deities from the magical universes of rock n’ roll and science fiction. Irreverence here is its own form of rebellion.

“What their paintings make gloriously visible is what crucially sets Aboriginal art apart from the work of the alienated New York school of Abstract Expressionists with which it shares visual similarities: a vibrant social world bustling with the beautifully mundanity of daily life that, for them, art brings together into a single web of collective experience”.

Wow!!!